|

One of the more inspirational books I have read over the last couple years is “A Surgeon in the Village,” by Tony Bartelme. The book describes the professional journey of an elite American neurosurgeon, Dr. Dilan Ellegala. Burnt out after years of high pressure schooling and hospital training, he travels to a rural hospital in Tanzania, largely to relax and depressurize. In a country with a population of 60 million, there are only a handful of neurosurgeons, and a clear hierarchy of medical staff that does not necessarily follow ability. Ellegala identifies a talented AMO (Assistant Medical Officer) who has little more formal training than a paramedic, and teaches him brain surgery.

While among our trainees we have had a few with engineering degrees, some of the more talented and capable have had only a high school education. By capable, I mean that they can independently and correctly run and interpret a geophysical water exploration program. One such student is Onen Martin Comboni. Outside of his work in local rural water supply, Comboni trains and performs with a talented and moving dance troupe of Acholi youth. On our one day off, they performed for us in a small village neighborhood on the outskirts of Gulu where they train. Similar to Ellegala’s trainees as well as our Geoscientists Without Borders/IsraAID water exploration program, the dancers are not picked through auditions following years of training. They are largely orphans and marginalized youth, with many coming from challenged families often still suffering from fallout of the civil war. What money that is raised from performances is then used to fund education as well as the many instruments and costumes that the troupe uses in the Acholi dances. And the dancers are spectacular! Many of the dances have a courtship theme. This undoubtedly motivates the Acholi youth, though it placed a few of us Muzungu in slightly awkward positions when invited/coerced on to the red clay dance courtyard. One simply cannot refuse to participate as dance is fundamental to Acholi culture, and to how people are perceived in the community. Also, as the women in at least one of the courtship dances carry lukiles, or small axes, one simply does not refuse the offer to go on to the dance floor when the blade is hooked around the back of your neck, as is the practice. I bought a lukile for my wife Leslie Bauman Gotfrit as a gift in the market.

0 Comments

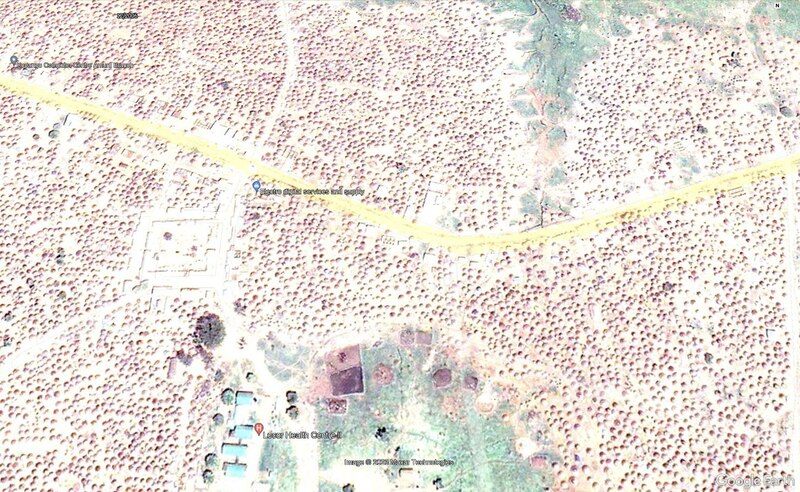

One of our Geoscientists Without Borders Project water exploration sites was deep in Amuru County, not so far on Google Maps, but 2 ½ hours driving each way. The site was chosen between IsraAID and the County Water Authority. Driving is not the best use of our time. On the other hand, if we don’t go to these remote villages, no one else will.

And the drive to Angakani was fascinating. We drove through the Amuru trading center (i.e., medium-sized town strung out along a red earth track) which, toward the end of the civil war, became the largest of the 200 “protection” camps in Northern Uganda. There is little remaining evidence of the Amuru camp, but in the 2006 Google Earth imagery one can clearly see the thousands of closely spaced grass huts that comprised the camp. Generally, I avoid asking direct questions about the civil war period, especially to the women and those that may have been of child soldier age during the conflict. But as we passed through Amuru on the tightly packed bus, I turned to Richard who was next to me. I knew he had been to all of the camps as a volunteer distributing food (maize, cooking oil, soy beans, and lentils) for NRC (NRC - Norwegian Refugee Council), ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross), and WFP (World Food Programme). For some reason, it seemed like the moment to ask a question I had never asked. “Richard, I always hear of two narratives. You were in all the camps. Were they really protection camps or outdoor prisons intended to punish the Acholi people?” He replied in what I have found to be typical, understated Acholi fashion. “Sure, some people did not want to be there, but they were forced to leave their villages.” I did not let up. “Come on Richard, the camps were horrible places with the highest mortality rates on the planet: malaria, cholera, typhoid, HIV, Ebola.” He responded, and perhaps he was only supporting my statement to end the conversation. “Sure, you are right. Everyone hated it. They all wanted to return to their villages. There was not enough food or water. Very crowded. People had no money. The soldiers guarding the camps had money, and brought with them HIV and Ebola.” As the war wound down, survivors of the camps were disbursed into smaller satellite camps closer to their home villages, allowing them to begin to rebuild their homes and gardens, even if they were not all capable of establishing safe water supplies which we are doing in this project. As far as I have seen, the satellite camps were often in horrible locations like swamps or areas devoid of springs, as they were temporary and previously uninhabited. On the return drive, and only from curiosity, and to the annoyance of our entire team as the driving was already too much, I asked to stop in the Amuru townsite to collect a few drone images of the relic camp area. "Just 10 minutes!" Big mistake. Even before I had pulled out the drone, an aggressive crowed immediately gathered around me. Moments later, in this distant, dusty backwater townsite, a heavily militarized-10-pickup-truck-Presidential convoy drove by only a few meters away, further raising the tension. President Museveni was the leader during the LRA civil war and established the IDP camps. I just wanted to get back on the bus and disappear. Serina, Proscovia, and Richard came to my rescue in Acholi. “Hey, he has come here to bring water to villages in Amuru County!" The crowd screamed back, "these Muzungu say they send money, but the money always stays in Kampala and they never come.” Richard shot back, “open your eyes! He is here in front of you! We are coming from Agikanyi. We will be back to drill a well in 2 weeks!” The tension subsided a bit. But retreating to the bus did not feel like an option. I quickly launched the drone. I handed the I-Pad with the real-time 120 m altitude viewing over to the village leader to divert the attention away from me. The drone landed, and the Amuru crowd wished us a safe journey – "Wad Mabeh!" A foundational assumption to our borehole repair and drilling program is that groundwater from a borehole is healthier and safer than water from a spring. Any hydrogeologist as or humanitarian worker in the WASH (water, sanitation, and health) sector is taught that the ground surface, and clays in particular, protect against the infiltration of animal and human waste into groundwater, and that the earth acts as a filter, removing toxic contaminants along the groundwater flow path, including dangerous bacteria.

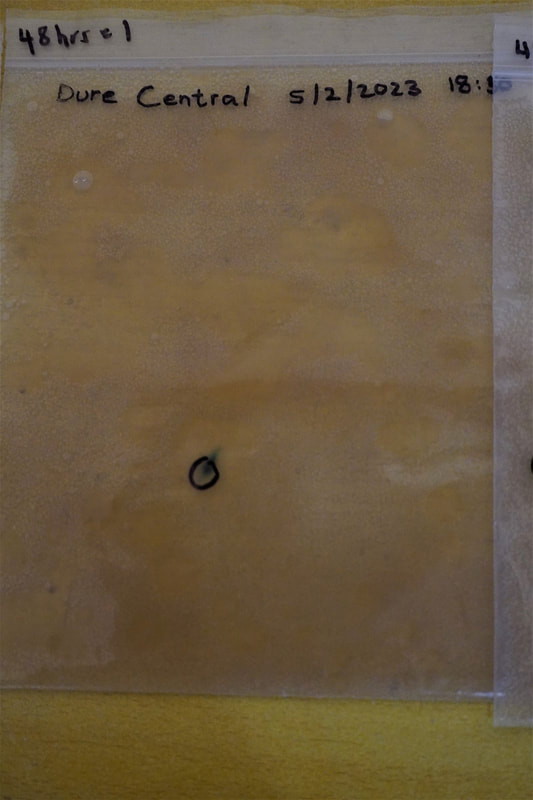

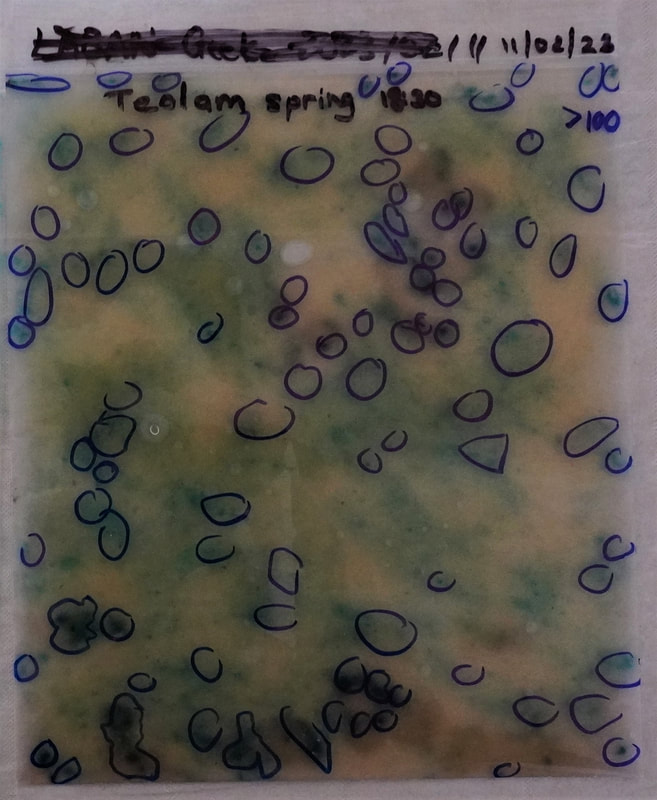

But is this really true? Is that crystal clear African stream less safe than that rusty old hand pump where cows, goats, and chickens are gathered? Is that spring flowing from a hillside actually more of a threat to human health than a handpump where women are collecting water, washing clothes, and cleaning pots? In the past, I always simply accepted that in rural Africa, groundwater is good, surface water is bad. After almost every talk I have given, the question is raised “did you test for bacteria”? My answer is always a “no.” No incubator. No electricity. Difficult to transport chemicals. Unreasonably strict hygiene requirements for handling samples in the field. It simply was not possible. In this Uganda campaign, though, largely at the urging of IsraAID's Selda Edris and BGC’s geochemist Kate Robey, we used a relatively new test kit developed by Aquagenx that requires no incubation, no electricity, no difficult-to-transport chemicals, and is relatively simple to implement. At each handpump repair site, including a few of our repair sites from our 2018 Geoscientists Without Borders program, we have tested the water for E. coli. Meanwhile, at all of the exploration sites where villages lack a water well and are reliant entirely on springs or rivers, I have collected surface water samples also for E. coli testing. I always do this myself as I get the chance to see the area beyond the immediate village, I can pick up a bit of Acholi language from the parade of villagers that always accompany me, and I get a better sense of the level of effort people expend to gather water when they have no village handpump. The results and conclusions have been clear and consistent. Of the 11 handpumps we sampled for E. Coli, all were within safe limits of between 0 and 4 CFU (Colony Forming Units). This even included 2 handpumps we installed in 2018 and 2 we repaired in 2018. In comparison, I sampled 9 springs, each of which was serving as the main water source for a community. All of the springs had high to extremely high CFU counts, with 4 of the springs having counts greater than 100 CFU. Most of these water spring-dependent communities complained of diarrhea, typhoid, and cholera. As bucolic and sleepy as bacteria counting, water spring sampling, and geophysical surveys may seem, field work has its moments. Yesterday, near the village of Agikanyi, hunters set fire to the forest to drive out the small mammals. The forest erupted into multiple walls of flames towering above the trees, first moving away from our survey and sampling area, and then, with a shift in the wind, moving directly toward the village spring, our crew, and the village. I was watching the smoke, sitting in the village drinking tea and eating my first Acholi donut of the morning while contemplating my second. I was listening to the somewhat panicky chatter on the radio about the flames jumping the valley – but people can run. But I then heard that the flames were within 20 m of the cables, and I was running as fast as I could downhill, donut in one hand and camera in the other. Cables cannot run, and can only be pulled. A photo of the normally unshakeable Serena showing a bit of concern is posted. How polite and patient are the famously warrior-like Acholi people? We have divided ourselves into two groups, an exploration crew and a well repair crew. Yesterday morning I was working with the exploration crew in the Acholi village of Teolam. When we run our cables across a walking path or clay track, we trench a very narrow slit in which we drop the cable, and then cover the micro-trench with clay or sand. A massive charcoal-laden lorry or a stampeding herd of ankole cattle could pass over this without damaging the cable.

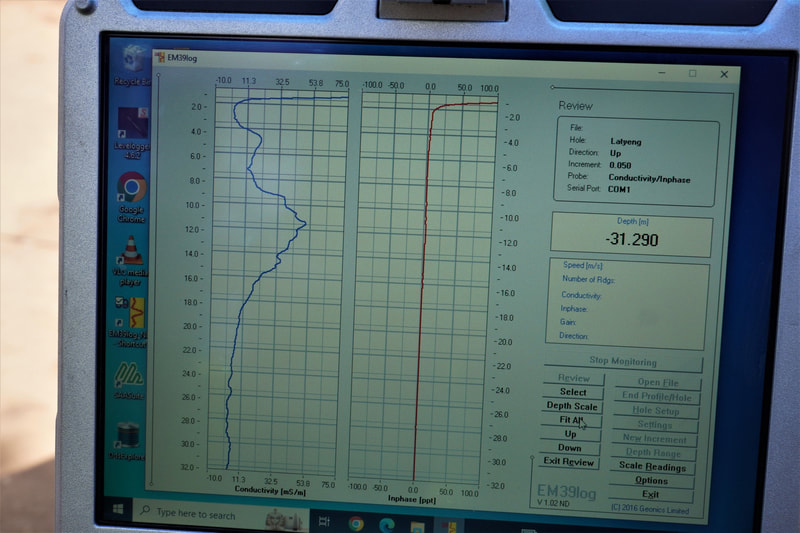

Yesterday, a man on a motor bike stopped at the cable, graciously asking to pass. His very pregnant wife, on the back, was in labor, and they were rushing to the health clinic. Randy Shinduke and Christy Rouault did not think long, and let them pass. Personally, I would have asked them to pose for a photo first, but I was sampling Teolam’s existing water source, a 300 m distant spring. There are no better words to describe the spring than filthy and dangerous. Sure, one could be a bit more science-like and call it turbid with a high e-coli count. The unprotected spring is about 6 m X 6 m. Not so much a spring as a seep dug out from the side of the Gulu-to-Kitgum highway. There is essentially no flow, and the water is opaque. Women and children cross the highway in the pre-dawn hours to take water before the animals drink, though this sequencing is likely irrelevant to their health. The villagers are fully aware that they suffer from periodic typhoid and cholera outbreaks, and chronic diarrhea. Teolam certainly needs a water well. Meanwhile, 2 km away, at the village of Latyeng where the well repair crew was working, there was a party going on – a mega, African bull elephant-sized festivity – something akin to what Moses likely saw when he descended from Mount Sinai and the ancient Israelites were regaling around the Golden Calf. When I arrived in Latyeng in the early afternoon, the Acholi village women and the Acholi women on our well repair crew were celebrating the repair of their well. I must acknowledge that Tara Coultish, Kate Robey, and Linda Harrison on the well repair team held their own, while Landon Woods threw his lot in with the masterful Acholi drummers. A filing cabinet-sized speaker and a car battery had been hauled from I don’t know where. Acholi music was blasting with songs about jealous second wives, the strength and beauty of Acholi women, the longing of Acholi men returning from war, and certainly much more than was translated for me. Chickens were being butchered. Food was being cooked and eaten. The science was still going on – isotope sampling, water chemistry, field iron analyses, bacteria sampling – but no one except a few Wazungu (Swahili for white people) seemed to care much as the people of Latyeng were now, at least for the foreseeable future, free from relying on their own highly contaminated, unprotected spring as a water source. We replaced the mongrel mix of cracked PVC and galvanized iron components with more expensive but far longer lasting stainless steel hand pump parts. And as the dancing raged on, the 20 liter jerry cans continued to line up faster than they could be filled until there was a line of more than 60 containers waiting for water. After waiting out two years of Covid-19 and then an outbreak of the Sudan Ebola virus, 5 colleagues (Landon Woods, Randy Shinduke, Tara Coultish, Christy Rouault, Kate Robey), an astrophysics student (Arnaud Michel), another one of those Invermere B.C. photographers (Linda Harrison), and Paul Bauman are back in Northern Uganda 20 days after the country was declared Ebola free. And while the White Nile offered a physical barrier and some protection for Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army (the LRA), from Ugandan forces to the south, the singular passage across the Karuma Bridge likely helped safeguard Northern Uganda from any Ebola cases.

We are once again funded by the Society of Exploration Geophysicists' humanitarian foundation Geoscientists Without Borders, along with generous support from our company BGC Engineering and its humanitarian foundation BGC Squared, a grant from the Kingston-North Kitsap Rotary Club, and a very generous equipment donation from Guideline Geo AB. Our partner here is, once again, the now not-so-small Israeli NGO IsraAID. IsraAID has been providing our on-the-ground logistical support and, most importantly, the community engagement. In particular, IsraAID was tasked with identifying at least 10 Acholi villages, schools, or health clinics highly dependent on water wells that are no longer functioning, and 10 villages, schools, or health clinics with no reasonable access to a safe source of drinking water. The fatigue of moving 50 pieces of luggage across the globe, going from -20 C to +35 C, and trying to accomplish something significant within our first few days has been exhausting. It is all just a warm-up, though, as in two weeks our plan is to be carrying out a water exploration program in a far more challenging and desperate area, near-famine conditions Kakuma and Turkana County. Most field days, this geophysical gig feels like a theatrical rendition of Louis Sachar’s YA novel “Holes”. If you have not read it, “Holes” follows the epic wrongful punishment of Stanley Yelnats who is sent to a youth incarceration site in the Texas desert where all the teenage internees endlessly and pointlessly dig holes in the desert pavement. For us, most days involve painstakingly and often with great effort and sometimes disappointing results, pounding hundreds of sensors into the ground, and then taking them out. Repeat, repeat, repeat.

If the United Nations deems that access to “Clean Water and Sanitation” is a human right, who in Zimba is considered human enough to have that right? OK, I am paraphrasing the late and very great Dr. Paul Farmer speaking about access to medical care, but the notion is equally valid, if not more so regarding water. How can one see young children and young mothers with infants walking kilometers with filthy buckets to gather water from mud puddles, yet be so close to Lake Kariba, the world’s largest manmade reservoir?! How can one travel for so many days and not see a trace of electrification, yet be so close to the Kariba Dam, one of the largest hydroelectric dams in the world?! The World Bank, who financed the Kariba Dam, has the mandate of providing “long-term economic development and poverty reduction by providing… such as building schools, providing water and electricity…”.

It is 4 AM and the roosters are already rocking this hilltop. Given the depths of poverty in Zimba District, the quantity of livestock is remarkable. As it has been explained to me, livestock are only rarely to be eaten. They are four-legged bank accounts. Should the rains not come in November, livestock can be sold, and food purchased. Successive seasons of drought are then a calamity, of course

Without exception we have found the Tonga people to be gentle, generous, and grateful for our efforts. As greetings are an act carrying great import in any Tonga interaction, the four of us from BGC have all learned the basic greetings of mwabuka buti (good morning), mwayusa buti (good afternoon), kwasiya buti (good evening), twalumba (thank you), and a few others. Any greeting is usually accompanied by a right hand over the heart, and a gentle and silent clapping of cupped hands

Beep! Beep! Beep! That is the sound the gas monitor in my waist pocket made indicating that there was no oxygen as I descended into the pre-1945 sewer manhole on the Muranowska street side of the Mila 18 command bunker in Warsaw. My legs kept stepping downward, but the three Warsaw municipal sewer workers, each of whom stepped on the scale at a few weight classes above me, cranked me up to surface as if they were master puppeteers.

|

Categories

All

Archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed