|

Seequent, whose 3D geological visualization software we (Alastair McClymont, Colin Miazga, Eric Johnson, Paul Bauman, Chris Slater) used for our 2017 water exploration program in the Rohingya Refugee Camps of Bangladesh, wrote a short piece looking back at the project for World Water Day. What is particularly nice about the article, though, is that they embedded some of the 3D visualization interfaces so anyone can take a spin and not only get a sense of the process, but take a look at some of the geology, geophysics data, existing water wells, and aerial drone imagery as well. The link to the article is:

1 Comment

Yesterday, August 25th, I was at the computer preparing a talk for a Symposium at Duquesne Universisty on Global Sustainability. My working title is: “Water, Refugees, and Geophysics – Are Humanitarian Water Problems 'Our' Problems?” Nevertheless, when WhatsAPP started buzzing on my phone, and I saw the call was coming from Bangladesh, I still had to think for a moment whether or not this was "My" problem.

Colin Miazga and I had been planning since June to do a water exploration program in the Nayapara and Leda refugee camps. In June, 2017, the population of the former was about 14,240 refugees, and of the latter, 19,230 Rohingya. But with the final round of violence beginning August 25th, Nayapara increased to 35,000 Rohingya, and Leda to 23,000 Rohingya. We moved up our start date, and expanded our crew to five.

...from a November 7, 2017 short interview interview I had on the Calgary eyeopener.

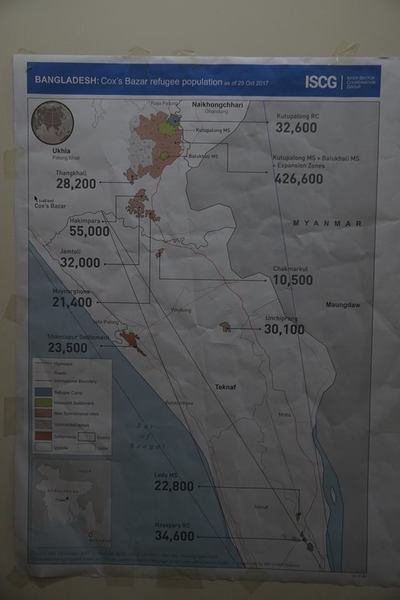

An October 26 interview with CBC Radio and TV about our upcoming water exploration program in the Rohingya Refugee camps in southeastern Bangladesh. As of today, there are about 830,000 Rohingya Muslims who have fled from Myanmar, with 620,000 having arrived only since August 25. The monsoon rains are ending, and they will need to move to yet undeveloped groundwater supplies.

Calgarians helping Rohingya refugees http://www.cbc.ca/listen/shows/calgary-eyeopener We geophysicists are very fortunate in the circumstances of our work in the Nayapara and Leda Refugee Camps. We are now interacting very closely with the refugee community. And we can have translation facilitated conversations about some quite intimate situations – water sources, distance to latrines, number of persons in the household, time spent collecting water, etc. However, the really heavy conversations about what happened in Myanmar are optional. Very much like after the Boxing Day Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, and very much unlike the refugees of Kakuma, I find the Rohingya are very open to talk about what happened in their homes and villages.

It is always very clear over the first day or two of an exploration program which individual is the most important member of the team. The learning curve is very steep for all 5 of us Canadians here. None of us speak more than a few words of Bangla. We do not have enough knowledge of the Bengali script to differentiate between the sign for a maternal health center and a tire repair shop. As we pull our cables through cities of plastic sheeting and mud, we have to constantly be aware that these are people`s homes; though, we do not have the cultural or language skills to properly excuse ourselves or ask for permission to pass

On October 29th, Alastair McClymont, Colin Miazga, Eric Johnson, Chris Slater, and Paul Bauman left Calgary and Vancouver with 24 pieces of baggage, most weighing 32 kg, for a two week water exploration program for the Rohingya Refugees in southeast Bangladesh. We left before the sun rose on Thursday, arrived in Dhaka after midnight on Saturday (minus three boxes of cables), and were menage a trois with UNHCR and Oxfam logisticians and WASH (WAter, Sanitation, and Hygiene) officers by Sunday afternoon. There was a lot to sort out – where would we go, how would we get there, and what exactly would we do.

Jet lagged with the 12 hour time difference and the stress of moving 560 kg of baggage from Calgary to Cox’s Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh, and none of us speaking a word of Bengali or Bangla as they often call the language, we worked in the more bucolic areas near, but outside the Nayapara and Leda Camps on Monday and Tuesday. Today, November 3, we began exploring for water on the edges of the camps themselves, beginning with Leda. The geology has already pulled a few surprises, but so have the Teknaf Peninsula of Bangladesh and the people that live there, including the Rohingya refugees. We are just beginning to figure out the geology; and, we are just beginning to comprehend what has happened in Myanmar since August 25th, and what is now going on within the now 850,000 person Rohingya refugee population in the southeastern most corner of Bangladesh. |

Categories

All

Archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed